Raise Achievement and Realize Priorities

Alice Lai and Joseph Costello

In many middle and high schools across the country, the most misused resource is time. Students have a limited number of hours in each school day, and demands on that time are growing at an aggressive rate. School and district leaders are facing an unyielding push for more customized electives and career-oriented programming. Wanting to ensure students feel comfortable and safe in their school communities, many schools are also seeking to weave in time for student social-emotional wellbeing. The many demands on student time often result in schedules that may be inadvertently undercutting essentials such as core instruction and differentiated intervention.

To deliver for students and realize district priorities, district leaders need to manage the precious resource of time strategically and methodically. But building a school schedule that optimizes opportunities for students often feels like an impossible task in the face of staffing constraints (e.g., available FTE, needed licensure, staff preferences), building space limitations, and budgetary pressures. For these reasons, in many schools and districts across the country, scheduling gets reduced to a technical task. The unlucky person assigned to build the schedule resorts to moving the proverbial “puzzle pieces" around as best as possible. The task of scheduling is considered successfully completed so long as students and teachers have their course and room assignments.

Many schools and districts simply roll their schedules over from year to year with only modest changes, despite the need for deeper strategic structural or programmatic changes. When questioned, school schedulers often reply, “That’s just the way we have always done it.” District and school leaders throw their hands up in frustration, knowing that the complexities of scheduling are preventing the implementation of the instructional priorities that drive achievement.

Having worked with districts for 20 years, District Management Group appreciates the tremendous challenges of scheduling but also understands the critical importance of managing the precious resource of time to achieve districts’ objectives. DMGroup has therefore invested heavily in developing expertise, identifying best practices, and building tools that help districts make the most effective and efficient use of teacher and student time. For elementary schools, we developed scheduling software called DMSchedules as well as software to schedule special education services called DMSchedules for Special Education. For the secondary level, we developed a methodical approach that is deeply grounded in scheduling as a strategic exercise, not just a technical one. Here we share our Secondary Scheduling framework and approach and highlight some key tips to help your schools build strategic, impactful schedules.

DMGroup’s Secondary Scheduling Framework

At its core, building and maintaining strong schedules for middle and high schools is an exercise in optimizing tradeoffs. How much time is enough for core instruction? How should a school create formal opportunities for intervention for students who struggle? Does the schedule need to include time for community building or social-emotional wellness support? What about the tradeoff between traditional academics and career and technical education (CTE)?

These are deeply strategic questions about how schools and systems should operate. The answer to each of these questions depends on the specific goals, priorities, and qualities of your unique school and district. What an urban school district considers to be an ideal high school schedule might be a terrible option for a rural school. Even schools from similar communities may approach how they schedule their time and leverage their staff in radically different ways because of their distinct needs and educational philosophies.

The research on secondary scheduling confirms this connection. The goals and priorities of a schedule are what give it meaning. As the noted education researchers Williamson and Blackburn point out, “Without clear goals, the schedule is merely a plan for organizing teachers and students; when guided by goals, the schedule becomes a tool to positively impact teaching and learning.”1

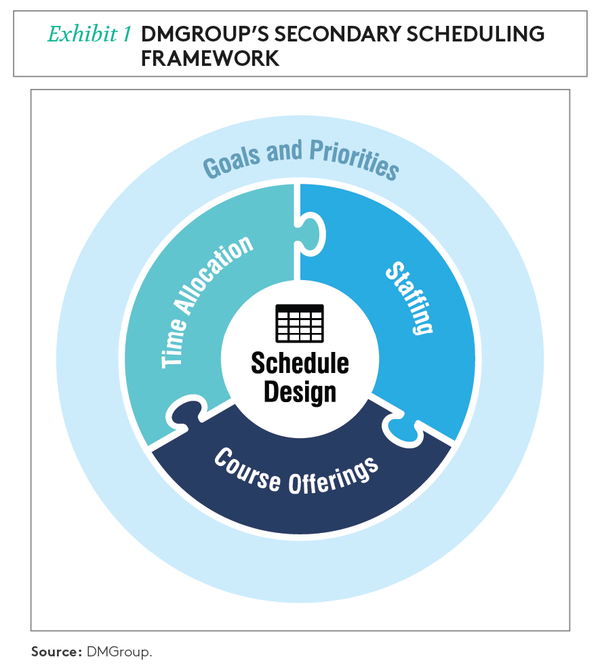

It is in this spirit that DMGroup developed its secondary scheduling framework (Exhibit 1). Of utmost importance to designing the schedule—and therefore encompassing all aspects of scheduling—are the goals and priorities: these must underlie all schedule design decisions and tradeoffs. With goals and priorities firmly in place, focus then shifts to determining the appropriate time allocation within the bell schedule, the necessary course and program offerings, and then the detailed plan for leveraging staff members. Using this framework, school and district leaders can create strategic and thoughtful secondary schedules designed to deliver the strongest results for students. This framework serves as the foundation for DMGroup’s Secondary Scheduling Institute and our custom secondary scheduling and equitable staffing consulting engagements.

Tips for Building Strategic Secondary Schedules

Emanating from our framework and based on our experience working with hundreds of schools across the country as well as our extensive research, District Management Group has developed a methodology and a series of tactics to help design schedules to achieve your district’s goals. While we cannot communicate our methodology and all our tactics in this short article, we provide here an overview of seven key tips to help design and build strategic, results-driven secondary schedules. We invite you to contact us to hear about our approach in more detail and learn how to create secondary schedules that help you meet your strategic objectives.

1. Approach scheduling as a team sport

Secondary schedules involve every person in the building. In fact, few features of schools are as personal and contentious as the building schedule. Before embarking on any scheduling redesign work, we believe it is essential for the school or district to assemble a scheduling team composed of key stakeholders (usually six to eight people, often including administrators, schedulers, counselors, and teachers) from across the building or district. Essential voices must be included in the conversation.

By having key stakeholders and decision makers at the table from the beginning of the process, schools create a collaborative and results-focused approach. Redesigning a schedule requires extensive change management, and creating a scheduling team allows for collaboration from the start and fosters greater understanding as key tradeoffs for important scheduling decisions are weighed.

2. Set clear priorities for your schedule

You can schedule anything, but you can’t schedule everything. Indeed, the biggest misstep schools make is trying to fit everything into the schedule — math intervention, guided reading, world language, music, expansive specials, the list goes on and on. When the schedule tries to do too much, few things are done well. The more things you add in, the more time you take away from what you already have.

Scheduling decisions therefore need to be grounded in clear goals and priorities. We always begin our work by asking members of a scheduling team to write out their priorities. This step is all too often overlooked, perhaps because the priorities are assumed to be well understood, but it almost always reveals multiple, sometimes conflicting priorities.

The scheduling team’s work together must begin with discussing, defining, and then clearly articulating the agreed-upon priorities for their school and schedule. It is also helpful to define the logic model behind identified priorities. What is it about the identified priorities that will bring about change or success in the school? This reasoning gives schedulers the focus and guidance they need to manage the endless tradeoffs that emerge in the process of building a schedule.

With agreed-upon priorities as the north star, the team must then distinguish between “must-haves” and “nice-to-haves” within the schedule. For example, do all teachers need common planning time? How should a student with multiple needs (special education, multilingual, etc.) be scheduled for electives? Prioritizing means that you have to say no to some great things. Collectively deciding on the “must-haves” versus the “nice-to-haves” allows districts and schools to provide coherent guidance for the people tasked with building and managing the schedule.

3. Maximize time on instruction

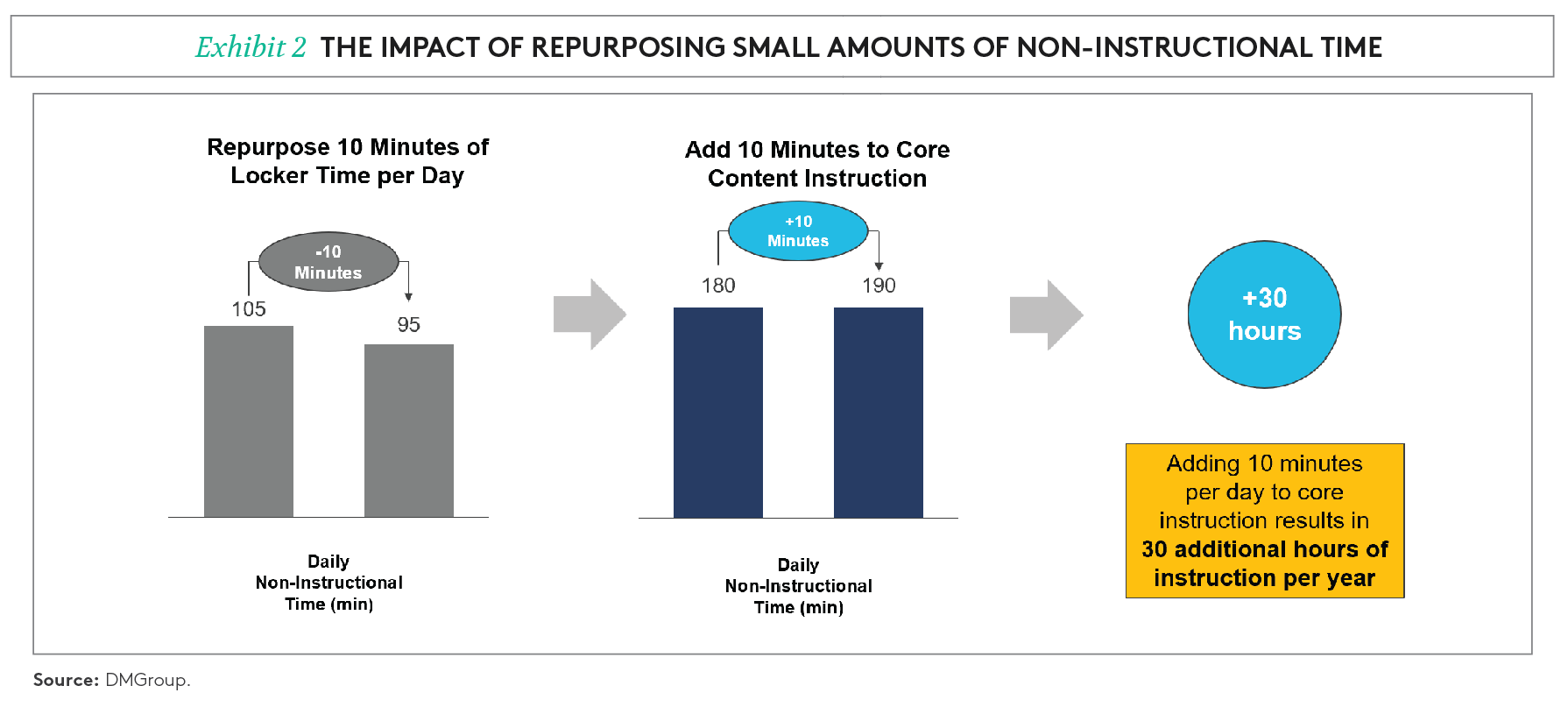

To create effective schedules, schools must closely examine how much time they spend on instruction compared to how much time is spent on non-instruction. In many schools, past practice has led to exceedingly long passing periods or transition time or misused non-instructional time such as homeroom. You might think a couple of minutes wouldn’t make a big difference. However, repurposing relatively small amounts of time can make a massive difference over the course of the school year. For example, one district decided to repurpose 10 minutes of locker time that was at the beginning of each day and allocate it back to instructional time—specifically, core content time. Over the course of the year, repurposing those 10 minutes of locker time each day added up to an additional 30 hours of instructional time (Exhibit 2).

As you reflect on the length of time dedicated to instruction, you should also consider how the time you allocate for each course or subject corresponds with its curriculum and academic standards. There should be coherence between them: for example, if your math curriculum requires 60-minute blocks for implementation, you should be sure that you are providing students and staff with sufficient time.

The big takeaway here is to know how much time is devoted to core, non-core, and non-instructional time and to ensure that students are provided ample time and opportunity to learn based on the stated approach.

4. Select a schedule model that fits your priorities

Questions we are frequently asked are “What’s the best schedule model? Is it block scheduling? Is it a traditional eight-period schedule? What’s the ‘right’ number of courses for a student to take at one time?”

Many are surprised to learn that research shows there is no single scheduling structure that is the “silver bullet,” and no “right” number of courses for a student to take at one time. Instead, research shows a strong positive relationship between academic learning time and student achievement. The more time a student has to learn for a given subject, the more they will learn. The essential caveat: time must be used effectively. And using time effectively in the schedule requires that all students and staff know why a specific schedule model was selected and how the time was intended to be used.

There is a wide variety of bell schedule models and structures used across middle schools and high schools. In general, three dimensions drive the design of secondary schedules:

1. Number of periods per day

2. Number of days in a cycle

3. Number of terms per year

Choosing a schedule model requires that you consider some inherent tradeoffs. For example, the number of periods in a day and over a cycle drives the total amount of time that students spend on core instruction. Depending on how students access core classes, the more periods that are added to the day lead to fewer total minutes students spend in each class. Alternatively, adding more periods can create more elective opportunities for students.

Period length only impacts student outcomes when teachers use that time effectively. The more time students have to learn, the more they will learn; however, that is assuming that they have an effective teacher and time is used appropriately, so providing adequate training and support to teachers on how to best use the instructional time available is critical.

Another important consideration is that different schedule models can have massive financial or staffing implications depending on how teacher caseloads are structured. The number of periods a teacher can teach in a day according to the teacher contract significantly impacts the efficiency of a schedule.

Switching schedule models can transform outcomes for schools and districts provided that the decision is motivated by thoughtful priorities. Each schedule model comes with implications, pedagogical and financial, and changing the schedule structure can have a domino effect. As you think about potential schedule models, think about their implications. Grounding the design of your schedule in your priorities allows you to determine which schedule type will best meet the needs of your students and district. It also forms the narrative for why the change in schedule is needed.

5. Analyze course enrollment and adjust course offerings to align with student need

Schools of all shapes and sizes deal with the common challenge of which classes to offer. Interesting and rigorous course offerings help to define schools, and they are often deeply personal, tied to the incredible educators who teach them.

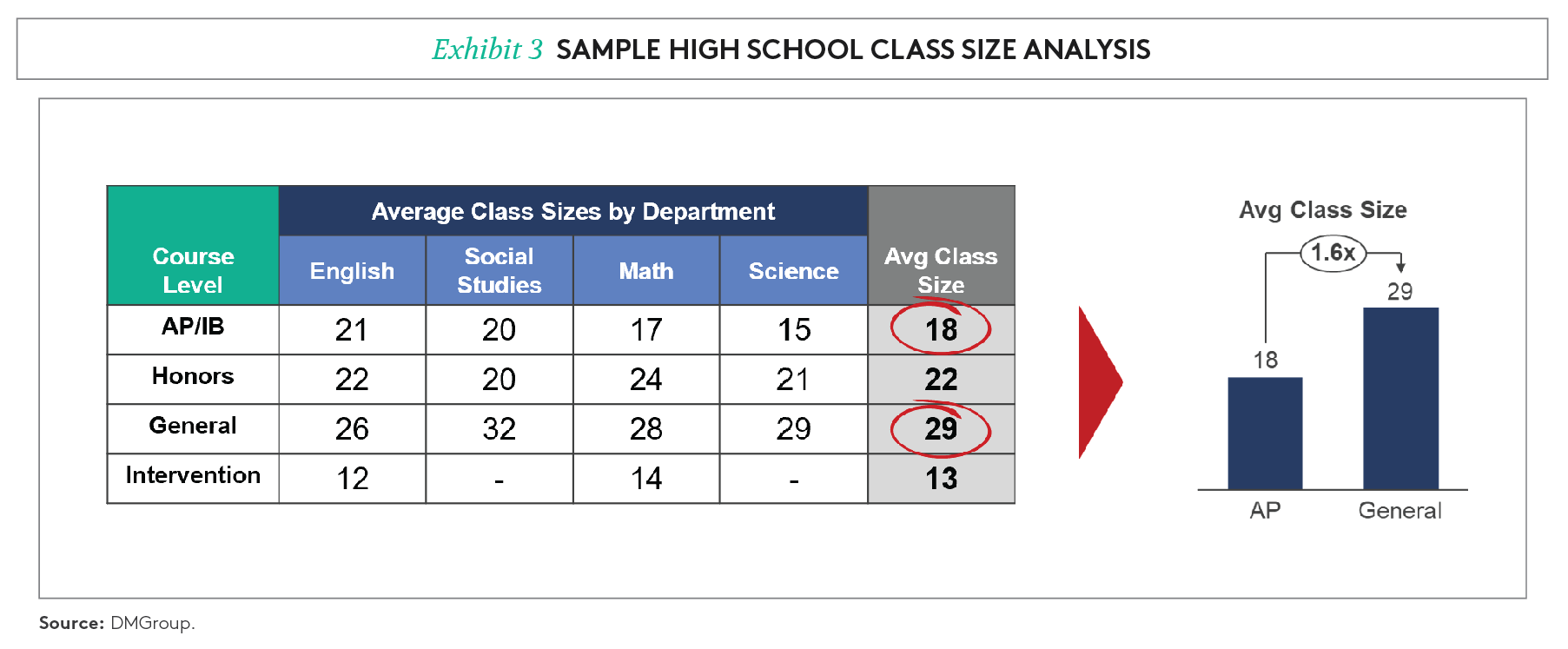

In many schools and districts, course offerings are taken as a given, rarely updated or examined. Analyzing course enrollment across course sections can be a great proxy for understanding whether course offerings are suiting the needs of students and if a school’s approach to staffing and scheduling is unintentionally benefiting a small subset of students. While schools and districts regularly calculate average class sizes, these figures may mask more nuanced trends. A more detailed analysis might show that disparities exist in average class sizes between different types of classes (core, elective, advanced, interventions, etc.). In many districts, regular-level core classes often have the largest class sizes, resulting in an unintentional investment in small class sizes for electives and advanced classes (Exhibit 3).

Reviewing courses with low enrollment can help identify courses that may be less popular or less suited to the changing needs of students. With careful scheduling and advanced planning, districts can reduce the number of low-enrollment courses without limiting student choice. Tactics that can be particularly effective include setting minimum class size limits, merging similar courses, and rotating specialized offerings.

Engaging teachers and other stakeholders in discussions about low-enrollment courses prior to building the schedule helps set expectations and avoid conflicts and disappointments. Waiting until significant portions of the schedule are already built and completed before discovering that certain classes must be eliminated can create disappointment for teachers and already-registered students.

6. Build in opportunities for intervention for students who struggle

Research and DMGroup’s experience working with hundreds of school districts suggest that one of the most powerful levers to raise student achievement is to build extra time into the schedule for targeted intervention opportunities. Many elementary schools have executed this strategy successfully in recent years, but secondary schools face unique challenges to integrating extra-time blocks into the schedule due to the greater variety of classes, the complexity of secondary staff schedules, and the different needs of students at that stage of their education. While intervention is difficult to schedule, providing these opportunities for students who struggle is critical.

Secondary schools often provide intervention by squeezing extra help into the same class period while students are receiving core instruction or by adding opportunities outside of the school day. Interventions come in a variety of forms, from co-teaching, push-in, or specialist support to implementing a separate curriculum for struggling learners. More help and more adults are provided, but not more time to learn.

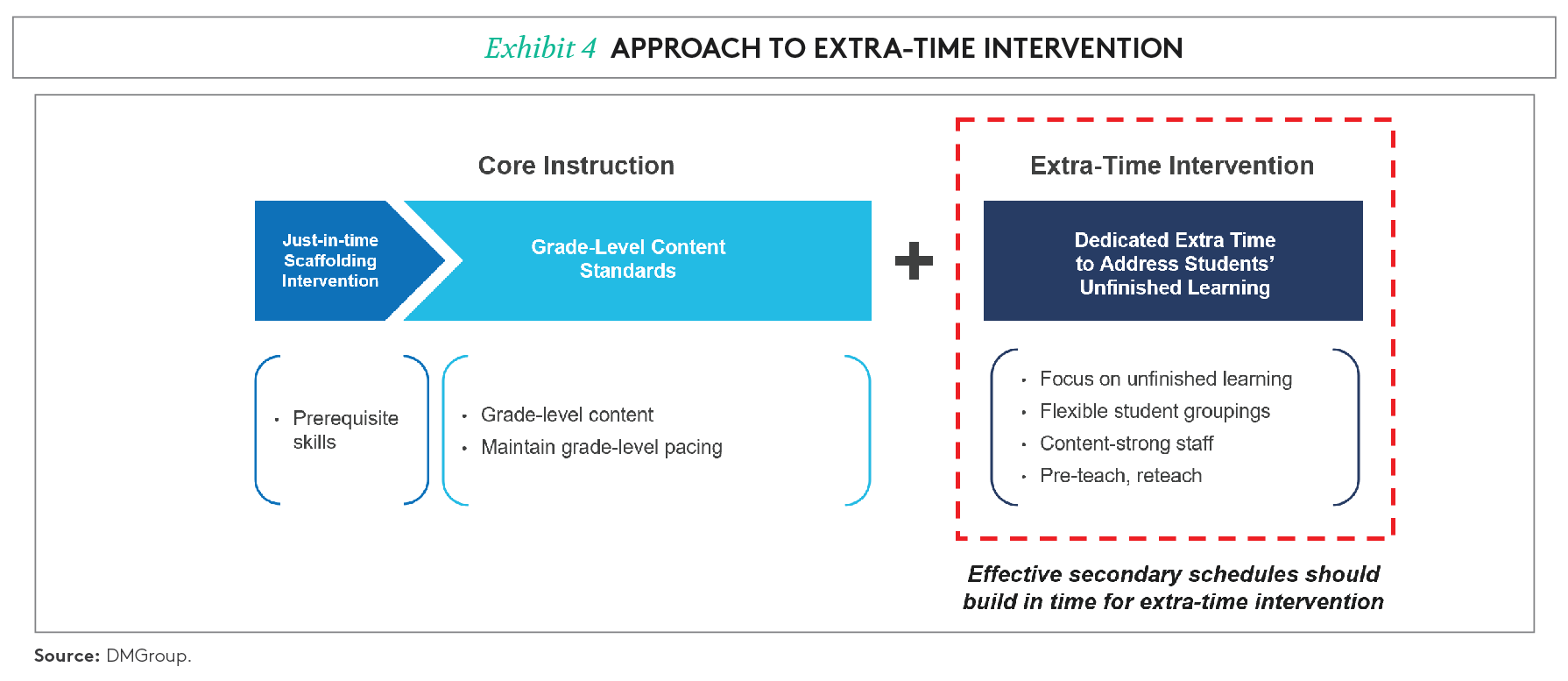

Best-practice research calls for extra time for interventions, not “instead of” time. This means that students who struggle are exposed to a first presentation of the content—100% of their current year materials—during core instruction, which allows them to be fully immersed in the classroom experience, learn from peer questions and interactions, stay socially engaged, and have the benefit of first being exposed to the material from their skilled core-instruction teacher. Then, in an extra period, students receive the interventions and supports they need to fully master the material (Exhibit 4).

Secondary Level Reading Program

At the secondary level, intervention supports most often include English and math, but, in some districts with significant achievement challenges, it is vital to include foundational reading intervention support as well.

Reading skills for struggling readers are distinct from the skills taught in English/ELA, which focus on interpretation, analysis, discussion, and writing. An extra period with an English teacher is not sufficient for struggling readers, who require the specific support of highly skilled and effective teachers of reading. Secondary students who struggle with reading should receive at least 60 minutes of additional time each school day focused specifically on reading, with explicit teaching strategies for comprehension.

7. Match staffing to student enrollment and need

Every principal, superintendent, and CFO asks how many of each type of teacher is needed each year. Using current guidelines for class size and teaching load, determining the FTE needs for each subject, department, and school should be straightforward. First you might begin with setting a class size target, perhaps 25 students per section, and a teaching load requirement, perhaps five sections per FTE. By dividing the number of students projected to enroll in a given course by the class size target, the district arrives at the total number of sections the department needs to staff.

Using teaching load rules, a district can determine its specific staffing needs. For example, with a class-size target of 25 students per section (except for 20 students in extra-help classes) and a teaching load of five sections per FTE, a school might calculate that it needs 7.4 FTEs to staff its math department.

However, when a district is faced with needing a partial FTE to meet staffing requirements, a typical solution is to “round up” to 8.0 FTE and schedule a few more sections, marginally reducing the number of students per section. Expert schedulers look for opportunities to maximize the impact of every resource when only a partial FTE is required. Districts can rethink what to do when course enrollment suggests not every position would have a full teaching load at current class size targets. Some approaches to leveraging staff more strategically include maximizing staff-sharing between schools, using part-time staff, or replacing a reduced section of an existing course with an intervention section or a new elective aligned with the school’s strategic direction.

Conclusion

Scheduling will always include tradeoffs and difficult choices—it is a challenging task. But scheduling does not have to be an activity that frustrates school and district leaders and keeps them from achieving important objectives. In fact, when approached methodically and strategically, scheduling can open the door to increased student achievement and better support for teachers.

Best-practice scheduling acknowledges that the structure of the schedule is not the end-all-be-all choice that determines a schedule’s success. Different scheduling structures can support key district priorities. Strategic scheduling can radically expand opportunities for schools and districts. With careful advanced planning, school and district leaders can transform scheduling from an obstacle that frustrates them to a powerful tool for achieving district priorities and boosting student learning.

We invite you to learn more about our framework, methodology, strategies, and tactics for developing powerful secondary schedules that can help you achieve your goals and, most importantly, deliver for your students.

1 R. Williamson and B. Blackburn, The Principalship from A to Z (Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education, 2009), chapter M—Managing School Schedules.